My high school (grades 11-12) lesson plan, were I able to present it to students, would be a way to get them to ask themselves why it is that they make assumptions about individuals based on their assumptions about groups (i.e. what are the stereotypes they hold, and why do they hold them to individuals).

Essentially, the project would have four distinct lessons (each of which will be listed here in the present tense, for simplicity's sake):

ONE: Students view several stock images of stereotypical people ("gay-looking" guy; African-American in what could be gang colors; white biker, posh white woman) and discuss what they assume about the person - what is the easiest way to identify the person, how do they act, what are their values, how do they get along with others, etc. After icebreaking with several of these, students see a few images of Subcontinental and Central Asian Muslim men (who basically look like what we consider the Taliban to look like) and discuss those same questions, as well as the assumptions we have about the ostensibly monolithic culture to which the men belong. Is there a difference between making assumptions about people within the U.S. and making assumptions about people outside the U.S.?

TWO: Students visit the Asia Society's show and focus written attention on works by the following artists:

(note: this image is made up of thousands of photos of the inside of a slaughterhouse)

The students pick one artist to write about and then fill out a worksheet with questions on two sides; on the first side, they are to answer the questions based on what they assume BEFORE reading any of the museum's explanatory text. On the second side, they are to answer AFTER they've read all of the explanatory text, and reflect on how they were correct and/or incorrect.

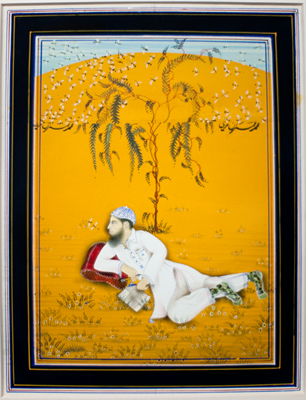

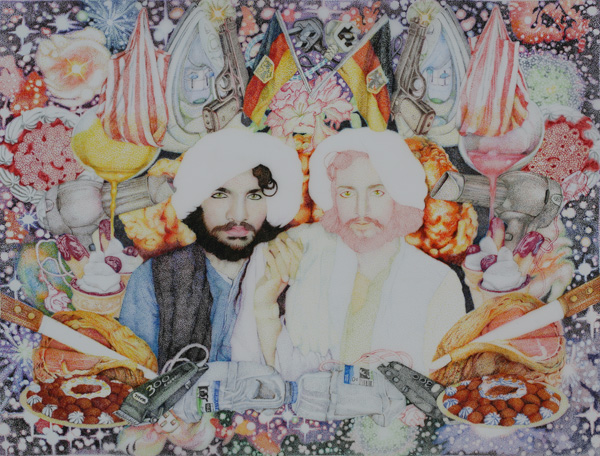

THREE: Students look at slides of works by Qureshi and Butt, who directly work with subverting our assumptions about Pakistani Muslims (Qureshi uses traditional Persian miniature painting to show devout Muslims engaged in nonthreatening activity; Butt depicts Taliban-lookalikes in dreamy, sort of homoerotic portraits surrounded by consumer goods and sci-fi-looking guns). The students then each pick a type of person who is considered "threatening" to our mainstream American culture, and then (through a combination of photocollage and/or painting) show that person engaged in an activity which is so mundane, yet realistic for them to do, that it 'humanizes' the figure and somewhat undoes the threat. As I said in the class in which I explained my project: "Even Nazis brush their teeth."

FOUR: Students consider the ways in which they've made and tested assumptions about other groups of people, and plan out a "portrait as they see me" - this is not a self-portrait, per se, but rather a portrait of themselves as the stereotype that they feel they are seen as by people who don't know them (and wow, that's a clunky sentence!). Students will consider why they're stereotyped - it's likely not just their skin color, but also their mode of dress, their body language, their speaking volume on the train, etc. What are they projecting intentionally and unintentionally? What's being assumed about them, and what's being read accurately about them? A teenager who feels that his skin color makes people scared of him might exaggerate that skin tone, depict himself as even more threatening. The stereotyped version of him- or herself is then to be engaged in an activity that they themselves do, to show that each student has a life which is not the stereotype that they are often conveniently fit into by people who don't know them personally. That same teenager might have a baby nephew who he dotes over, or be a gardener, or like to listen to Haydn's string quartets, etc etc etc.

I was very pleased to get to present this project in my class, and the feedback was very good. It was pointed out to me that this lesson could be modified to work with other art shows (really any show of artwork which uses identity politics as a theme could work) and other grade ranges (depending on the students, of course). I'm thinking that this will definitely be a project that I try to teach once I get a job somewhere and have a sense of the school and the students.

I'm really interested in getting students to recognize how they can intentionally represent themselves, through their artwork but also through their quotidian activities and their specific composure. I'm also interested in getting them to deconstruct their own assumptions about other groups. If I get the chance to teach some form of this project, I think it will be one which is remembered for a long time by the participating students, and I think that the artwork will be heartfelt, engaged and intellectually stimulating.

It might also be really angry. So much the better.

The show at the Asia Society itself is really good, by the way, and totally worth going to (I think it's free on Friday nights, so you can go like a true New Yorker).