Sunday, October 18, 2009

Saturday, October 17, 2009

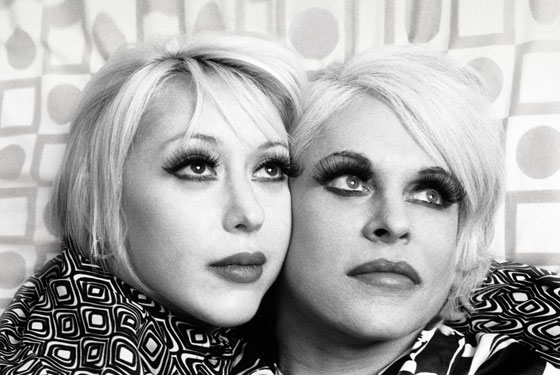

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and the obliteration of Self

Both aspects of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge amalgamated as a Vitruvian "Pandrogyne"

I feel bad that I didn't get to see (or write a blog entry about) Invisible Export's show of artwork by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, entitled "30 Years of Being Cut Up," until the exhibition was literally in its final weekend. The body of work displayed on the walls was interesting not only on its own (the collages range in intent from Fluxus-inspired antagonism to magic spellcasting) but also as a facet of one of the most interesting, if at times perplexing, examples of defining and owning one's own identity.

Beauty is in the Eye, 2006.

Red Well, 1999.

Unless noted, artwork images are from the Invisible Exports show linked at the top of this article.

More are here (very much Not Safe For Work).

In talking about P-Orridge, correct use of gender-specific pronouns will get very complicated. Please bear with me -- I've tried to use the artist(s)' terminology and delineations wherever possible.

For those readers who aren't familiar with Genesis P-Orridge in the many phases of his (and now he/r) career, here's a really brief synopsis: Born as Neil Megson in 1950; formed the performance-art collective COUM Transmissions around 1969; turned COUM into the pioneering electronic-noise/industrial music act Throbbing Gristle in 1975, recording and touring with TG until the bands' dissolution in 1981; that same year, formed another music group, Psychic TV, releasing music under that band name through to the present day; introduced the subcultural "modern primitive" trends of body modification and neo-paganism to the 'alternative' audience through the 80s and 90s; as Throbbing Gristle, Psychic TV and other musical acts, has released over 200 albums, including a Guinness-record-setting 70 in one calendar year (as Psychic TV).

But here's where it gets really interesting:

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (left) and Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (right). Image from New York Magazine's great recent interview

In 2003, P-Orridge moved to Brooklyn with his second wife, Lady Jaye, née Jacqueline Breyer, and began an ongoing experiment in body modification aimed at creating one pandrogynous being named "Genesis Breyer P-Orridge". The two began this project by getting matching breast implants, then approximately $200,000 worth of plastic surgery to resemble each other. They dressed identically, copied each other's mannerisms, and both replaced the pronoun "I" with "we," "he" or "she" with "s/he," "his" or "her" with "h/er." I'm going to use these pronouns from here on, both for simplicity's sake and out of respect.

Two Into One We Go, 2003 - moving towards a single being composed of two identical individuals.

They became individual facets of a single, idealized being. They abandoned the concept of Self.

Lady Jaye died in 2007, and since then, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (a construct originally composed of Genesis P-Orridge and Lady Jaye Breyer) has existed in the body of one person. S/he ("they"?) declares in interviews and on the web that Lady Jaye still exists as a living part of the pandrogenous amalgam "Genesis Breyer P-Orridge." The surgeries and hormone therapies continue, and the past few years have been busy for Gen - Throbbing Gristle have reformed and toured, MoMA has scheduled a lecture in March, 2010, and most recently, thirty years' worth of collages have been exhibited in a well-received gallery show in the Lower East Side.

Untitled (Mail art to Robert Delford Brown), 1975. Gender fluidity is hardly new to he/r.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

A collaborative art project from an ethnically/culturally diverse group

I like to think that my son is responsible for the sweeping gestures in the center third.

This is a detail shot of a long fingerpaint-on-craft-paper panel, painted by the feet of the "Hummingbirds" (1-2 years) group at the daycare center at which my son spends five days a week.

I know that this is hardly "high art," but it's the piece of visual...um, stimulus? that I've been most struck by over the past few weeks, no doubt in part because of its associations -- my child is painting!! -- but also because of its beautiful colors and 'strokes.' And considering that I'm more than willing to get visual stimulation from rust patterns and peeling paint in the subways, I think it's fair for me to post this. I'd love to get a good-quality image of the whole painting.

Artistic cross-culturalism: hard to pull off (who'da thunk it?)

Kerry James Marshall's "Watts 1963," 1995

Marshall's work deals directly with his identity as an African American, while also directly engaging his position as a figurative 'narrative images on canvas' painter, working in a tradition that is directly linked to European painters such as Caravaggio, Rembrandt, and El Greco (along with African American artists such as Charles White and American folk artists of many ethnicities).

At the end of the 20-minute video on Marshall and his work, our class briefly discussed Marshall's use of imagery and compositions from European culture, and Rebecca asked the class why we thought it was that it's so much more common for minority artists to work within the hegemony's forms of art, rather than the other way around - Europeans looking for, and acknowledging, influence from non-Western/non-hegemonic cultures. Jackson Pollock (whose exposure to Navajo sand painting early in his life likely affected his signature period of 1947-1950 or so) and Pablo Picasso (whose break from the 19th Century makes a lot more sense if you've seen African and Oceanic masks) were brought up as rare exceptions to the rule that cultural influence trickles downward more often than upward.

Part of the problem, I think, stems from the typical distinction that Western culture makes between "art" and "non-art" (which I address a bit in the first substantive post to this blog). Artists tend to want their work to be tied into that great big millenia-long conversation that traces a long, convoluted line between the cave paintings in Altamira and whatever's happening in Chelsea galleries this month. As such, it behooves them to explicitly draw from high art so as to say "My art belongs in this history."

Warhol put a Byzantine-style gold background on a modern-day icon.

This graffiti, at 5 Pointz in Queens, refers to Rembrandt to say "I'm a High Art painter, too."

By comparison, explicitly referring to folk art, popular culture and/or 'non-art' in one's work may make it harder to be taken seriously by the art establishment. Sure, the gallery scene may love you, and you may have a great couple of years of sales, but don't bet your paychecks on getting into the Art History canon.

Takeshi Murakami's pop-culture appropriations are probably not going to be in the equivalent of a Janson textbook in 100 years.

Another issue that I see deals with culture outside of the art world. When someone related to the hegemony ("The Man") appropriates aspects of a non-hegemonic culture (even Picasso), there's often a feeling of, if not paternalism, at least noblesse oblige - like a representative from High Culture is deigning to give a nod to Low Culture's masses. It's like seeing a white undergrad in a dashiki and cowry shells in his hair, whose knowledge of colonial-and-post-colonial African history comes mainly from listening to Fela Kuti records while stoned.

Maybe I'm just being grumpy, but I find Marshall's connection to The School of Athens to be much more interesting, and much gutsier as a statement of identity, than a contemporary painter in London attempting to draw a connection between his work and, say, Ellis Ruley.

Or, even worse, there's the condescending version of "acknowledging another culture," like this statue by Erastus Dow Palmer, Indian Girl, or the Dawn of Christianity, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

This is colonialist condescension at its finest: a statue of a topless, ostensibly "Indian" woman, gazing thoughtfully and lovingly at the cross in her right hand, while getting ready to drop the feathers (representing her primitive, pagan religion, of course) in her left hand. According to the Met's description, the allegorical sculpture symbolizes ""the Dawn of Christianity Upon the Aborigines … [and would] symbolize the first impression of civilization upon the native of this country."

Holy crap, wow!

And for what it's worth, I'm not so sure that Paul Simon's Graceland is free of condescension, either.

Monday, October 12, 2009

Myrtle-Broadway stained glass: a nice statement of local identity

Here are some photos I took recently of the stained glass panels on the above-ground subway platform at Myrtle/Broadway (J, M, Z) in Brooklyn. They represent the rich and broad contributions of African Americans and Latin Americans to American musical culture.

Individual panels pay tribute to jazz...

...with recognition of contributions from the Islands...

...and the South's position as the birthplace of the blues...

Individual panels pay tribute to jazz...

...vocalists...

...drummers...

...keyboardists...

...more drummers...

...and the South's position as the birthplace of the blues...

...but none of the panels make mention of hip hop.

"Daddy, I'm a bit confused."

In all seriousness, the lack of acknowledgment of hip hop makes me assume that the artist and/or the MTA folks who commissioned the panels don't see it as worth mentioning in a monument to African American contributions to popular music. Which is odd, considering how quickly it's all but taken over the mainstream of pop music, here and abroad. I wonder if that has to do with the general outsider's belief that all hip hop is about violence, drug-dealing and misogyny, or if it's the fairly common and well-documented disdain that the jazz community holds for hip hop (not only for what it says but also for the fact that it uses samples rather than live instrumentation, and sonic assemblage rather than traditional composition).

This is a shame, as the panels are a really important esteem-booster in an otherwise dank subway station (and neighborhood), but leaving out the past 30 years of musical innovation keeps these from being as broad a statement of identity and pride as they could be.

As an educator (-in-training), I try to remember that whatever my students' ethnicity or race, they're a member of many cultures and subcultures - and so I feel that giving a nod not only to the neighborhood's race, but also to the youth culture, would make this even more relevant to more people.

As an educator (-in-training), I try to remember that whatever my students' ethnicity or race, they're a member of many cultures and subcultures - and so I feel that giving a nod not only to the neighborhood's race, but also to the youth culture, would make this even more relevant to more people.

Subtle, guys.

Yesterday, I went into a Chase ATM on Myrtle Avenue on the Bushwick/Ridgewood border and saw about two dozen flyers for "ANACONDA Underwear."

Blatant in so many ways. Let's give a quick list:

Sexual:

More info about ANACONDA Underwear (marketing images, photos from the launch party, and ordering information) here.

On the other side of the flyer was this image:

Another ad which uses a pretty, sexualized Latina to sell a product that she wouldn't (necessarily) use: "cigar wraps" (which are used to roll marijuana much more often than tobacco). I'll give the copywriter the benefit of the doubt and assume that no connection was intended between the bikini-clad woman and the phrase "PASS IT AROUND."

The blog for this product is pretty remarkable, with such posts as "The slowest burning cigar is the wrap king cigar wrap. Its the best cigar used to roll a blunt. It burns the slowest compared to other cigars. Slowest burning. " and "If John and Kate plus 8 goes on a date and smokes 3 wrap king cigar wraps that they bought in a local store. With 3 packs of wrap king 3 everybody rolls one"

Blatant in so many ways. Let's give a quick list:

Sexual:

- The oiled, well-muscled man has a sexy woman hanging off of him. She's making eye contact with the camera (acting as the interlocutor acted in Renaissance paintings), as if she's flirting with the viewer rather than the muscleman.

- The "ANACONDA" brandname and logo, to say nothing of the slogan "NOT FOR THE AVERAGE MAN," make it pretty clear that this underwear is being pitched as "only for real men" (more specifically, men with larger-than-average penises).

- Both models appear to be of minority ethnicities (a label so broad as to be meaningless, I know) and look like they're on the 'young, cool and sexy' end of the spectrum of people that you'd see on the street in Bushwick or parts of the Bronx. She doesn't have a generic 'model' face (her facial features aren't leaning towards Caucasian, as is the case with a lot of non-Caucasian models). He's got two or three distinct and different tattoos visible: over his pectoral muscles, a handlettered slogan (LIVE NOW, DIE LATER") and the outline of fire; around his neck and down his chest, a set of Rosary beads and cross. This implies a 'tough but pious' persona and makes explicit reference to a Catholic background that's typical of Latino/as in America.

- Back to that "NOT FOR THE AVERAGE MAN" slogan: this could also be read as a statement that the target audience for Anaconda Underwear (Latinos and African-Americans, from the website's photos) has bigger penises than the target audience for other underwear (whites). This alludes to the longstanding stereotype of more "animal" sexuality (and less intellectualism) which was ascribed by whites to minorities long ago, and which has in some ways been used against the hegemony which came up with the stereotype in the first place (once most people decided that there wasn't anything wrong with being sexual).

- Black, red and yellow is pretty much the easiest, most basic, most high-impact color scheme to use in an advertisement or design. Red and black is often associated with fascism, and yellow and black is an aposematic color scheme in nature - think of honeybees, snakes, poison-arrow frogs. Perhaps the waistband, peeking up through a pair of loose jeans, would serve as a 'warning' that what's in the jeans is more than some women can handle?

More info about ANACONDA Underwear (marketing images, photos from the launch party, and ordering information) here.

On the other side of the flyer was this image:

Another ad which uses a pretty, sexualized Latina to sell a product that she wouldn't (necessarily) use: "cigar wraps" (which are used to roll marijuana much more often than tobacco). I'll give the copywriter the benefit of the doubt and assume that no connection was intended between the bikini-clad woman and the phrase "PASS IT AROUND."

The blog for this product is pretty remarkable, with such posts as "The slowest burning cigar is the wrap king cigar wrap. Its the best cigar used to roll a blunt. It burns the slowest compared to other cigars. Slowest burning. " and "If John and Kate plus 8 goes on a date and smokes 3 wrap king cigar wraps that they bought in a local store. With 3 packs of wrap king 3 everybody rolls one"

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Reasons I Still Love NYC #290: The Sukkah Mobile

Or is that a "mobile sukkah"? I saw this on the Thursday of Sukkot in Fulton Mall (which, if aren't familiar with it, is a huge, delapidated shopping district in downtown Brooklyn that is mainly catered to African-American shoppers). Hebrew-language disco was blaring out of the SUV which towed the sukkah.

It's worth noting that this particular sukkah is wrapped in an image of the late Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who some Chabad Lubavicher Hasidim believe to be Moschiach, aka "The Messiah" (and as such not really dead). These followers of Schneerson are a subset of Hasidic Judaism, itself a subset of Orthodox Judaism in America. As such, it makes a strong statement of identity -- of faith, of culture -- to drive through town towing his image behind your car. There's a building in my neighborhood, on the border between mainly-African-and-Puerto-Rican Bushwick (Brooklyn) and mainly-Eastern-European-Catholic Ridgewood (Queens), that has a photo of Schneerson on a bumper sticker on its door, with the words MOSCHIACH IS COMING in English. There's also a sign on the door advertising YOUR 1-STOP FOR ALL THINGS JEWISH. The Chabad Lubavichers are mostly based in Crown Heights, miles away. I've wonder if it's located so far from the Hasidic neighborhoods in Williamsburg (on the same subway line) because it needs to be distanced from the more prevalent Hasidic community.

On that same note, I wonder if the Sukkah Mobile drives through the Hasidic neighborhoods in Williamsburg (and now Bedford-Stuyvesant)? It might be more tense to do that than to drive through Fulton Mall, because Hasidim who aren't Chabad, who don't agree that Rebbe Schneerson was the Moschiach/Messiah, will know a lot more about, and quite possibly be more offended by, the yellow flags that flew on the back of the sukkah:

Friday, October 9, 2009

Willoughby Windows: There goes the neighborhood, here comes the art

Yesterday, I walked out of my cooperating school and towards Flatbush Avenue Extension, and found this interesting group exhibition installed on a to-be-demolished abandoned block of storefronts on Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn (in the Metrotech Center). The project was set up by the Metrotech BID and a group calling itself AdHoc Art - it includes works by:

While it's sort of overwhelming and disturbing to see that yet another block of downtown Brooklyn is being torn down (for condos?), it's good that someone realized that, at the very least, putting some artwork in the windows would be less depressing than just leaving the storefronts empty (as with elsewhere in the nearby Fulton Mall).

The show's only up until November 5th (note - it's been extended through March 2010), but hopefully that's enough time for the students I'm working with now to check it out at least a few times. It's always nice to discover this sort of thing in your neighborhood, and the project is only a block away from one of their two school buildings.

The view from one corner...

...and the other.

The bakery's window displays were filled by the always-enjoyable Ellis G, who will probably end up getting an entry on this blog soon.

Woven displays by Michael DeFeo

Collage/assemblage by Greg La Marche

Cycle's storefront forces me to yet again wonder if it really counts as "graffiti" when it's produced with the permission of an institutionalized space (even if that institutionalized space is only temporary).

Logan Hicks produced this evocative stencil image; I recommended it to one of my 12th-grade students who's spent most of the past month working on a finely-detailed stencil image of Biggie Smalls, Eazy-E, Bob Marley and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Another case of diminished signifiers:

This is a commercial hair-braiding salon in downtown Brooklyn, by the school at which I'm currently student-teaching. When I was in junior high school, I read an article somewhere that mentioned that braid patterns on African girls and women allowed researchers to trace the matrilineal heritage of a bloodline all the way back to individual tribes in Africa. This blew my mind.

I assume that that is less the case now that women can get their hair braided in any one of several braid patterns, by paying someone rather than getting braided by their mother or another woman in the family.

Baseball caps used to SIGNIFY (one particular) something

I've been thinking about this topic, and adding to it, since basically the first class this semester. Please bear with me if it wanders...

The thing is, baseball caps have undergone a significant shift in their significance (in the Saussurean sense, as in "what they signify, how they act as signifiers") over the last fifteen or so years. I'll demonstrate mostly using a Yankees cap, though it pains me to do so as a Red Sox fan, because of the historical significance of the Yankees (or their logo, at least) in this particular story.

This is your basic Yankees cap (it's 'on-field,' meaning it's what the team members wear). For a century, with some minor variation on the logo and fabric weight, this was likely to be the Yankees cap you'd see on someone. And it was a very simple signifier: "I like the Yankees. They're my team, and this is the hat they wear."

This started to change in the early-to-mid-90s, when Spike Lee approached New Era Caps (the company that makes mass-market caps for Major League Baseball teams), asking if he could commission a Yankees cap in red. This became a signature clothing item for Lee, and showed New Era that they could make much, much more money by decodifying what makes a Yankees cap a Yankees cap (and thus decodifying what a Yankees cap means, as I'll explain in a moment).

With the speed of anything marketed to and by the "urban" and "youth" markets, the change was immediate and highly visible: baseball caps no longer were locked to their 'regulation' colors, and a person who wanted his (or her) outfit to match the Yankees cap no longer needed to plan the outfit around the cap. Now it just takes buying a cap that matches the outfit.

As a result, the signifying aspect of the Yankees cap begins to chip away. That plaid Yankees cap could be a sign that you're a big fan of the team who is of Scottish heritage; it could also be a sign that you felt an item of clothing, ideally a cap, with those colors would best complete your 'look.' The baseball cap becomes about as significant as sneakers, which also have a community of collectors who are obsessed with acquiring the most outlandish, exclusive colors and patterns.

There's also a new submarket for "girl" caps, with any team's logo in white on a pink cap. We certainly couldn't have a woman wearing a plain Yankees cap, could we? How would we be able to tell she was female if she wasn't wearing a feminized version?

On a side note, there have been two mindsets with baseball caps for a long time; the 'urban' market (which is strongly correlated to, but not exclusive to, African- and Latino-descended people) often keeps their caps as clean and new-looking as possible, whereas the more hegemonic (white, mostly) portion of society tends to be a bit more comfortable with wearing "broken in" clothing (faded jeans, for example). This has led to pre-faded caps on one end of the spectrum, and flat-brim caps (with a different-sized brim, made to stay flat) on the other.

Those who buy the flat-brim caps do their best to keep them immaculate -- to the point that they're almost always worn with the stickers still attached. This serves two purposes, as far as signification goes: it says "I will only wear this hat so long as it is still brand-new" and also "this is a brand-name, authentic item for which the standard retail price is widely known." It's conspicuous consumption at its most basic.

By comparison, the 'broken-in' caps have bent brims, are colored with dye that fades quickly, and sometimes even come with pre-fab fraying on the seams. Affluent folks (and white folks in general, if I may perpetuate another stereotype) are more comfortable with dressing like they don't have any money.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention that I wear a more faded (mostly by being several years old) version of the Red Sox cap below, with the alternate logo rather than the standard "B" - I love the team (they were my hometeam when I grew up in New England) but much prefer NYC to Boston, and my hat sort of signifies that, I think.

With so many other statements signified now, the team-specific signification of baseball caps is remarkably diluted, to the point where the caps are essentially decoration before they're a statement of team allegiance. They no longer only say "I like the team that wears this cap" - they also say "I like this color more than the color the team wears," "I have this relationship with consumerism," "I come from this ethnic background and identify myself as part of this social community," etc.

With that being the case, is it any wonder that the flat-brim caps of teams outside the region are starting to show up on teenagers as the finishing touch on obsessively color-coordinated outfits? If you like a particular color more than the colors of your hometeam, why not wear the cap of a team whose "on-field" colors match your outfit?

I can't imagine that the high-school-aged guy on my subway car last week, who was wearing a purple shirt, purple shoes, and a pristine, stickered Colorado Rockies cap, was wearing the cap because he was a Rockies fan. Certain teams other than the Mets and Yankees have fans in NYC -- the Red Sox are a notable example, as are some of the old teams based in Southern and Midwestern cities (the Braves, the Cardinals).

However, when I see several guys standing together on the L train late at night, all of them wearing Kansas City Royals caps which match the royal blue elsewhere in their outfits, I can't help but wonder if perhaps the cap is being used as a gang signifier. Perhaps it's urban legend that "KC" is used sometimes to signify "Killer Crip," but I'm pretty sure it's safe to say that there are more gang members in Brooklyn than there are fans of the Royals outside of Kansas and Missouri nowadays.

The thing is, baseball caps have undergone a significant shift in their significance (in the Saussurean sense, as in "what they signify, how they act as signifiers") over the last fifteen or so years. I'll demonstrate mostly using a Yankees cap, though it pains me to do so as a Red Sox fan, because of the historical significance of the Yankees (or their logo, at least) in this particular story.

This started to change in the early-to-mid-90s, when Spike Lee approached New Era Caps (the company that makes mass-market caps for Major League Baseball teams), asking if he could commission a Yankees cap in red. This became a signature clothing item for Lee, and showed New Era that they could make much, much more money by decodifying what makes a Yankees cap a Yankees cap (and thus decodifying what a Yankees cap means, as I'll explain in a moment).

With the speed of anything marketed to and by the "urban" and "youth" markets, the change was immediate and highly visible: baseball caps no longer were locked to their 'regulation' colors, and a person who wanted his (or her) outfit to match the Yankees cap no longer needed to plan the outfit around the cap. Now it just takes buying a cap that matches the outfit.

As a result, the signifying aspect of the Yankees cap begins to chip away. That plaid Yankees cap could be a sign that you're a big fan of the team who is of Scottish heritage; it could also be a sign that you felt an item of clothing, ideally a cap, with those colors would best complete your 'look.' The baseball cap becomes about as significant as sneakers, which also have a community of collectors who are obsessed with acquiring the most outlandish, exclusive colors and patterns.

There's also a new submarket for "girl" caps, with any team's logo in white on a pink cap. We certainly couldn't have a woman wearing a plain Yankees cap, could we? How would we be able to tell she was female if she wasn't wearing a feminized version?

On a side note, there have been two mindsets with baseball caps for a long time; the 'urban' market (which is strongly correlated to, but not exclusive to, African- and Latino-descended people) often keeps their caps as clean and new-looking as possible, whereas the more hegemonic (white, mostly) portion of society tends to be a bit more comfortable with wearing "broken in" clothing (faded jeans, for example). This has led to pre-faded caps on one end of the spectrum, and flat-brim caps (with a different-sized brim, made to stay flat) on the other.

Those who buy the flat-brim caps do their best to keep them immaculate -- to the point that they're almost always worn with the stickers still attached. This serves two purposes, as far as signification goes: it says "I will only wear this hat so long as it is still brand-new" and also "this is a brand-name, authentic item for which the standard retail price is widely known." It's conspicuous consumption at its most basic.

By comparison, the 'broken-in' caps have bent brims, are colored with dye that fades quickly, and sometimes even come with pre-fab fraying on the seams. Affluent folks (and white folks in general, if I may perpetuate another stereotype) are more comfortable with dressing like they don't have any money.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention that I wear a more faded (mostly by being several years old) version of the Red Sox cap below, with the alternate logo rather than the standard "B" - I love the team (they were my hometeam when I grew up in New England) but much prefer NYC to Boston, and my hat sort of signifies that, I think.

Not particularly meticulous. Very Caucasian.

With so many other statements signified now, the team-specific signification of baseball caps is remarkably diluted, to the point where the caps are essentially decoration before they're a statement of team allegiance. They no longer only say "I like the team that wears this cap" - they also say "I like this color more than the color the team wears," "I have this relationship with consumerism," "I come from this ethnic background and identify myself as part of this social community," etc.

With that being the case, is it any wonder that the flat-brim caps of teams outside the region are starting to show up on teenagers as the finishing touch on obsessively color-coordinated outfits? If you like a particular color more than the colors of your hometeam, why not wear the cap of a team whose "on-field" colors match your outfit?

I can't imagine that the high-school-aged guy on my subway car last week, who was wearing a purple shirt, purple shoes, and a pristine, stickered Colorado Rockies cap, was wearing the cap because he was a Rockies fan. Certain teams other than the Mets and Yankees have fans in NYC -- the Red Sox are a notable example, as are some of the old teams based in Southern and Midwestern cities (the Braves, the Cardinals).

However, when I see several guys standing together on the L train late at night, all of them wearing Kansas City Royals caps which match the royal blue elsewhere in their outfits, I can't help but wonder if perhaps the cap is being used as a gang signifier. Perhaps it's urban legend that "KC" is used sometimes to signify "Killer Crip," but I'm pretty sure it's safe to say that there are more gang members in Brooklyn than there are fans of the Royals outside of Kansas and Missouri nowadays.

"They're like self-portraits that we didn't get to draw"

The most recent project for the 11th-grade class that I'm student-teaching was, in my mind, a really interesting group exercise, both in terms of the physical works it produced and in terms of the issues of representation it raised with the students.

The project was both simple and complex: each student posed for a headshot photo, which was then printed and cut into six equal squares (the 11th Grade art class has two sections of 6 students each). The squares were shuffled and handed out to all six students in each section - so that each student had a chance of there being some fragments of his or her own face, but a much bigger chance of fragments of others' faces. Each of the squares was to be reproduced on much larger (around 18x18) pieces of paper (using any black-and-white material - charcoal, pencil, ink, etc).

When all of the individual drawings were completed, they would be correlated, arranged and taped together so that the original photos would have been reproduced by up to six different artists.

Here are some of the results:

Then it came time to put the images together.

The project was both simple and complex: each student posed for a headshot photo, which was then printed and cut into six equal squares (the 11th Grade art class has two sections of 6 students each). The squares were shuffled and handed out to all six students in each section - so that each student had a chance of there being some fragments of his or her own face, but a much bigger chance of fragments of others' faces. Each of the squares was to be reproduced on much larger (around 18x18) pieces of paper (using any black-and-white material - charcoal, pencil, ink, etc).

When all of the individual drawings were completed, they would be correlated, arranged and taped together so that the original photos would have been reproduced by up to six different artists.

Here are some of the results:

(I absolutely love the one on the right, for what it's worth - the eyes are a remarkable combination)

The students loved making the drawings, and their exploration of materials and imagery was a lot of fun to watch and encourage. They were very supportive of each other while working - talking up each other's skill and in general sounding like they really loved the assignment.

At that point, several of the students (all of them girls) voiced frustration with "how I look." They weren't complaining about the individual drawings, or even pointing out the fairly obvious points in the assembled portraits in which one student's rendering was less exact than another's. To do so, after all, would break up the bonhamie they'd been enjoying for the last two weeks of studio time. Instead, they just complained about the whole "assembled" drawing. Strangely, they would say what they thought the drawing looked like other than them ("I look like a devilspawn," "I look like some kind of alien dog or something"), but they never said "this doesn't look like me."

One of the students explained to me "this is rough, especially for, you know, teenage girls, who are all self-conscious about everything in the first place. It's like a self-portrait that we didn't get to draw."

That last sentence is key: these drawings feel, due to their roughness, their basic materials, their scale, like the sort of identity statement that a high-school student would make in a piece of art. The identity, however, is removed from the hand of the artist(s).

It's a fine example of the tension that can result when someone recognizes that they aren't in control of their own representation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)